|

|

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means: electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

First edition 1993

Second edition 1995

Second printing 2017

Published by:

Aardsma Research & Publishing

412 N Mulberry St

Loda, Illinois 60948-9651

www.BiblicalChronologist.org

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 95-95068

ISBN 978-1-7372151-0-3

| List of Figures | 5 | |||

| List of Tables | 7 | |||

| Preface to the Second Edition | 9 | |||

| Dedication | 13 | |||

| 1 | Introduction | 15 | ||

| 2 | A Peculiar Phenomenon | 21 | ||

| 2.1 | Biblical People in Secular History | 21 | ||

| 2.2 | A Problem in Biblical Chronology | 25 | ||

| 3 | Some Biblical Hints | 27 | ||

| 3.1 | A Chronological Conflict in the Bible | 27 | ||

| 3.1.1 | A Judges – 1 Samuel Interlude | 28 | ||

| 3.1.2 | Acts 13 | 29 | ||

| 3.2 | A New Approach | 32 | ||

| 4 | Development of a New Pre-monarchical Chronology | 35 | ||

| 4.1 | Textual Matters | 35 | ||

| 4.2 | Finding an Anchor | 40 | ||

| 4.2.1 | Biblical Archaeology | 41 | ||

| 4.2.2 | The Conquest of Ai | 43 | ||

| 4.3 | Restoring the Biblical Text | 48 | ||

| 4.4 | A Simple Explanation | 50 | ||

| 4.5 | The New Chronology | 50 | ||

| 4.6 | Biblical Genealogies | 53 | ||

| 5 | Harmony Restored | 57 | ||

| 5.1 | The Exodus | 57 | ||

| 5.1.1 | The New Date | 60 | ||

| 5.2 | The Wilderness Wandering | 61 | ||

| 5.2.1 | Mt. Sinai | 62 | ||

| 5.3 | Palestine | 63 | ||

| 5.4 | Conclusion | 65 | ||

| 6 | More Harmony | 67 | ||

| 6.1 | The Time of Abraham | 67 | ||

| 6.2 | Joseph's Famine | 68 | ||

| 6.3 | The Missing Egyptians | 72 | ||

| 6.4 | Conclusion | 74 | ||

| 7 | Some Pre-monarchical Biblical People | 75 | ||

| 7.1 | Biblical Historical Persons | 75 | ||

| 7.1.1 | Cushan-rishathaim | 76 | ||

| 7.1.2 | The Pharaohs of the Oppression and Exodus | 78 | ||

| 7.1.3 | Joseph and Joseph's Pharaoh | 80 | ||

| 7.2 | Conclusion | 82 | ||

| 8 | Cities of the Conquest | 85 | ||

| 8.1 | Jericho | 86 | ||

| 8.2 | Other Cities | 90 | ||

| 8.3 | Conclusion | 93 | ||

| 9 | Miscellaneous Implications | 95 | ||

| 9.1 | Composition Dates of Old Testament Books | 95 | ||

| 9.2 | Habiru | 97 | ||

| 9.3 | History of Israel | 98 | ||

| 10 | The New Chronology in Perspective | 101 | ||

| 10.1 | Validity of the New Chronology | 101 | ||

| 10.2 | A Context for This Work | 103 | ||

| 10.2.1 | A Brief Historical Sketch | 104 | ||

| Bibliography | 105 | |||

| Index | 110 | |||

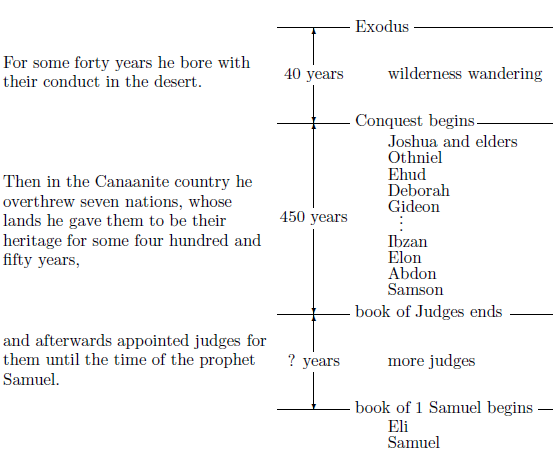

| 3.1 | Portion of Paul's recitation of Israel's history from Acts 13:18-20. | 33 |

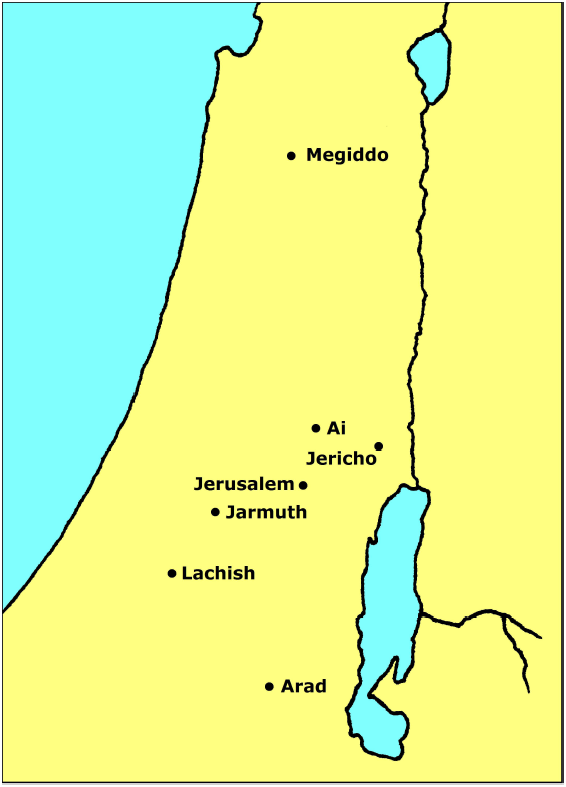

| 4.1 | Map of Palestine showing some of the cities at the time of Joshua. | 44 |

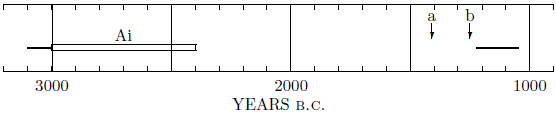

| 4.2 | History of Ai as reconstructed from archaeological reports. | 47 |

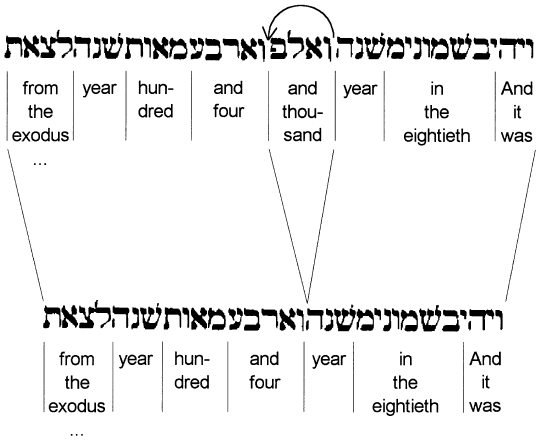

| 4.3 | Proposed copy error resulting in the loss of one thousand years from the present text of 1 Kings 6:1. | 49 |

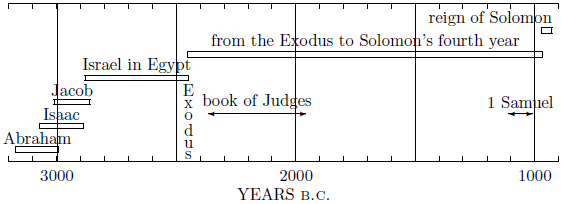

| 4.4 | Principal elements of the new biblical chronology. | 51 |

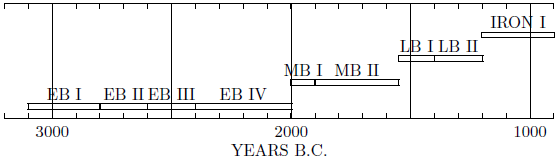

| 5.1 | The archaeological and historical time periods in the Near East during the second and third millennia. | 64 |

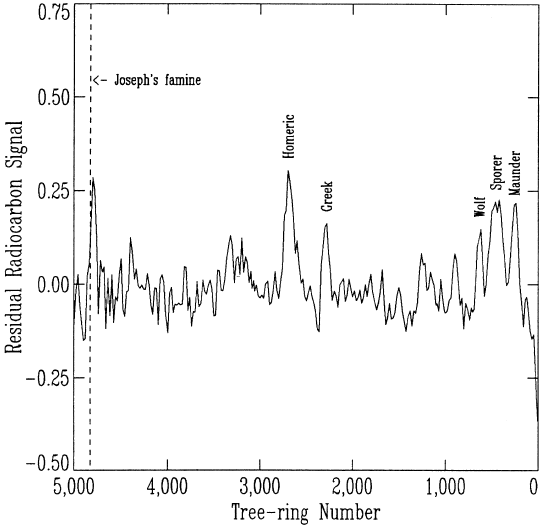

| 6.1 | Radiocarbon measurements on tree-rings and Joseph's famine. | 71 |

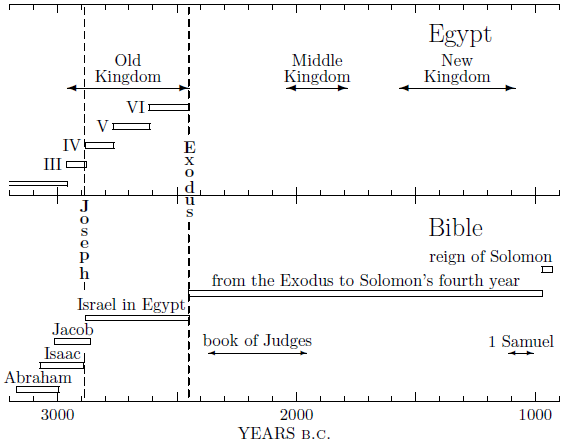

| 7.1 | Locating Joseph in the chronology of Egypt. | 81 |

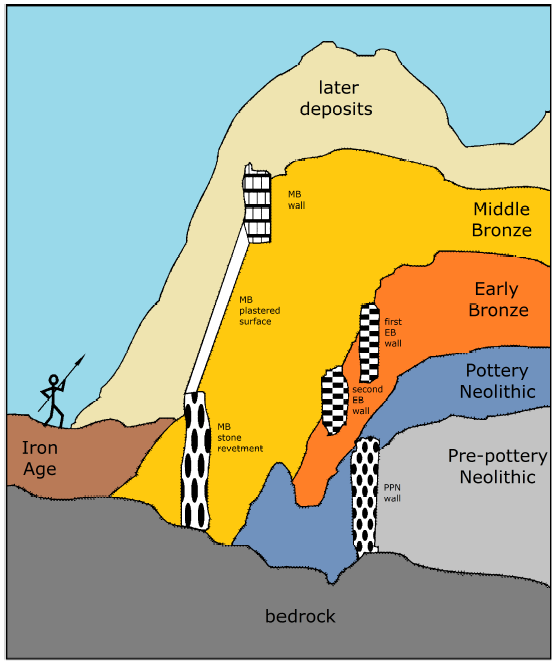

| 8.1 | Schematic cross section of the mound of ancient Jericho as revealed by modern archaeological excavation. | 87 |

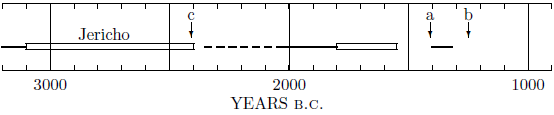

| 8.2 | History of Jericho as reconstructed from archaeological reports. | 88 |

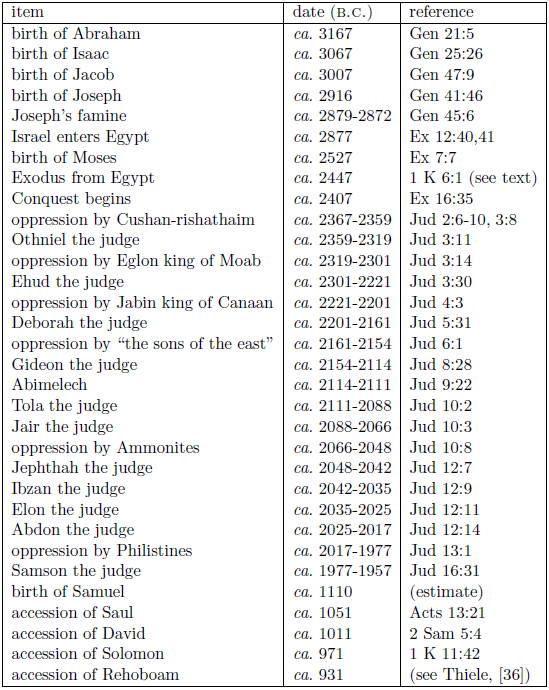

| 4.1 | Approximate dates resulting from the new biblical chronology. | 52 |

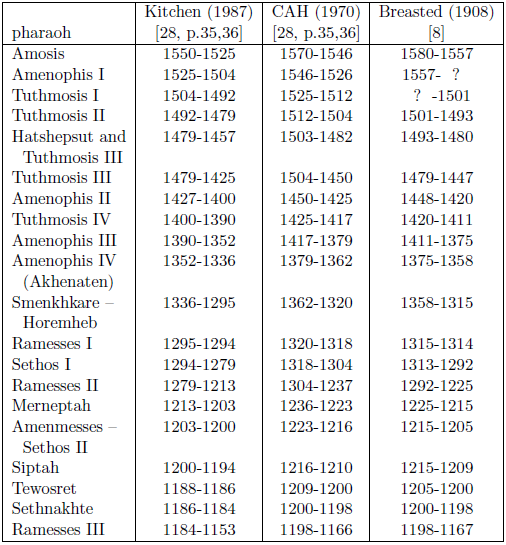

| 5.1 | Three chronologies of the New Kingdom of Egypt. | 59 |

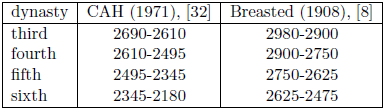

| 5.2 | Chronologies for the Old Kingdom dynasties of Egypt. | 60 |

The sociologists tell us that, for the most part, we believe things to be true, not because of the factual evidence demonstrating their veracity (which is the only reason why we should believe them), but because we have heard other "significant individuals" around us stating that they are true. This foible of human nature makes it rather difficult to get people – even highly educated people – to accept a radical new idea, even when the evidence in support of it is somewhat overwhelming. The difficulty is that very few will even bother to consider the evidence when what is being suggested departs radically from traditionally accepted ideas. In practice, it is generally necessary to first find and inform the few independent-minded individuals who are able to think for themselves and take a stand on the basis of factual evidence alone. These few can then function as "significant individuals" for others, and then these for yet others … until what had seemed radical becomes respectably commonplace.

Having had the simple thesis which is presented in this book, and the new biblical chronology which it gives rise to, rejected as "too radical" by more than one of the standard archaeological and biblical journals, I, in desperation, settled on publication of my thesis through this little book. It exists to find and inform the few.

This is now the second edition of this book. I am hoping that enough "significant individuals" will soon exist for my thesis to seem sufficiently mundane to allow for its publication in the mainstream literature – a goal which I continue to pursue. I cannot help but feel that old views must very soon be swept away, so forcefully conclusive do the objective evidences in support of my new chronology now appear.

I have had some opportunity to publicize my thesis to limited audiences at several conferences. I presented it to a gathering of theologians at the 44th annual meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society in San Francisco in November 1992. The response was quite positive. Last summer I presented it again, this time to a secular gathering of several hundred scientists at the 15th International Radiocarbon Conference in Scotland. The response of the majority of scientists gathered there was also favorable. These experiences have reinforced my conviction that hindrance to acceptance of my thesis is sociological only; objective individuals are generally quite impressed by the evidence when once they have been caused to consider it.

I find my experience (and reaction) with regard to criticism of the new chronology proposed by this book to be somewhat parallel to that experienced by Edwin R. Thiele, the biblical chronologist of the previous generation who untangled the chronology of the monarchic period. He reports, in the preface to the second edition of his important work:[1]

Criticisms fall into two main categories. On the one hand, certain members of liberal groups do not regard it possible for these numbers to have been handed down through so many years and so many hands "without often becoming corrupt." On the other, a few vigorously outspoken members of conservative groups view with horror any questions that may be raised concerning the absolute accuracy of any details in the Old Testament chronological data. Far apart though these two points of view may be, both rest on the same foundation of an a priori bias. Both categories have prejudged the questions at issue. Rather than permitting truth to be determined by objective investigation, both groups have pronounced a precursory judgment. Such, however, is not the attitude of true scholarship, nor is it in accord with biblical principles of religious faith and practice.

While reading through the first edition of this book, in preparation of this second edition, I was pleased to find that the form and substance of my argument did not need to be changed in any way. At the same time, I was struck by the fact that I had pared the argument to the bone in many places. I debated whether I should make this second edition a considerably fatter book than the first by fleshing out my argument and incorporating the new evidences I am now aware of. In the end I decided not to do so, for several reasons.

First, and foremost, I would like to preserve the unencumbered simplicity of the first edition. The thesis which I present in this book, though radical relative to traditional thinking, is not at all complicated, and its derivation and demonstration do not demand long-winded and contorted arguments. I am loath to give any other impression.

Second, I have moved on in my own research to the time before Abraham – the thesis of this book giving such research, for the first time, sufficient quantitative precision to hope to obtain reliable results and reach meaningful conclusions in this remote period. I find this work fascinating and absorbing; I am reluctant to set it aside even for the few weeks which would be required to add more material to the present book.

Third, I am now regularly publishing the results of my research through a bimonthly subscription newsletter called "The Biblical Chronologist."[2] Additional evidences pertinent to the thesis of this book are slowly being compiled there; it seems unnecessary to duplicate them here.

Finally, this choice perpetuates and reinforces my initial intention; this little book is meant to be a beginning – the introduction of a new idea – not the final, exhaustive word regarding it. Authentic biblical chronology research is necessarily a very large, interdisciplinary activity today. Time is the thread which sews together all historical studies – from the archaeological remains at Jericho, to the annual layers found in the Greenland ice sheet … to the history narrated in the pages of the Old Testament – and each of these studies has a legitimate contribution to make toward our understanding of the chronology of the past. My claim is that we have got the thread a bit snarled in this piece of the fabric we call biblical history, with the result that the overall garment of history is wrinkled and distorted to our perception. I have only ever aspired, in this little book, to show how to untangle the thread – not how to smooth all the wrinkles.

Gerald E. Aardsma

May 12, 1995

Loda, IL

To my mother,

Margaret,

and my father,

Jacob,

whose lives have been an example of faith worth following,

and

with special appreciation

to all who have encouraged me in this work.

You share the eternal reward.

The historicity of the Old Testament is currently facing a challenge of unprecedented severity. This challenge has arisen over the course of the past half-century, not from speculative theories, but from the hard data which have been dug from the earth by the spade of the archaeologist. Under attack is the veracity of the Old Testament books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, and Judges.

Many conservative Christian scholars and laypersons (to whom this book is addressed) seem unaware of the seriousness of the present situation. They are unaware of the great quantity of archaeological data which has been obtained in the past few decades, and of the apparently uniformly negative implications of these data for the historicity of the early Old Testament books. Yet the assertion, arising from decades of research in biblical archaeology, that the biblical books from Genesis through Judges are not at all historically accurate is widespread and rapidly gaining adherents.

Some who are familiar with the archaeological data have attempted to sidestep its seemingly unpleasant implications by asserting that the Bible needs no proof, its truths must be apprehended by faith. True though this may be, it misses the point rather badly. The current issue is not proof, it is falsification. The Bible clearly recounts the exodus of the children of Israel from Egypt and the conquest of Palestine under Joshua as if these were real space-time events which happened to real historical people. Those who are presently claiming that there never was either an Exodus or a Conquest – that the nation of Israel "emerged" in Palestine some other way – are at least implicitly claiming that the biblical record of these events is false. Now, we who call ourselves conservative Christians are not required to prove the Bible true, but we most certainly must be able to launch a credible defense against claims that it is false (1 Peter 3:15).

Many Old Testament scholars and biblical archaeologists have noted the disharmony which presently exists between biblical history (i.e., the written account of the past which is found in the Bible) and biblical archaeology (i.e., the material remains from the past which are dug from the ground) in the pre-monarchical period (i.e., the period of time before the Israelite kings). In 1984, for example, the late Joseph A. Callaway of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary – the director of a major excavation at the site of ancient Ai, among other accomplishments – observed [5, 449, page 72]:

For many years, the primary source for the understanding of the settlement in Canaan of the first Israelites was the Hebrew Bible, but every reconstruction based upon the biblical traditions has foundered on the evidence from archaeological remains.Callaway went on to conclude, somewhat tragically, in my opinion, that this lack of harmony warrants rejection of the historicity of the pre-monarchical biblical account.

Though I agree with Callaway's premise that "every reconstruction based upon the biblical traditions has foundered on the evidence from archaeological remains" I strongly disagree with his conclusion. Rejection of biblical historicity is not logically mandated until every possible "reconstruction based upon the biblical traditions" has been shown to fail, and this most certainly has not been done, as the following chapters will demonstrate.

The reconstructions which have previously been proposed and/or seriously considered by various scholars can be placed in one of several possible categories, depending upon their treatment of data within the following four areas:

Biblical history,

Biblical archaeology,

Biblical chronology, and

Secular chronology.

Reconstructions which take a low view of (i.e., treat as mythological, untrue, or of no real significance) biblical history are popular at the present time in non-conservative circles. Individuals who hold to such reconstructions regard the present lack of harmony between pre-monarchical biblical history and archaeology as proof of the legitimacy of this view. Having rejected the biblical account of the Exodus and Conquest they are busy trying to find alternative explanations of how the nation of Israel came into existence. (The Merneptah stela and the harmony of biblical history and archaeology after the origin of the monarchy prohibit them from supposing that the entire biblical account of Israel in the Old Testament is myth or late tradition.)

I believe that this view, though widely held, is mistaken. Since I have written this book as a biblical conservative to other conservatives, there is no point in discussing this non-conservative category any further here, except to note that the present volume is antithetical to it. The entire non-conservative synthesis of the pre-monarchical "history" of Israel, – with its concomitant negative implications for biblical historicity, inerrancy, and ultimately theology – will fail in direct proportion to the success of the ideas presented below.

Reconstructions which take a low view of standard biblical archaeology but a high view in the other three areas give rise to our first conservative category. Those who hold to the "early date" for the Exodus ( ca. 1447 b.c.) fall into this category. It necessarily denies the archaeological evidences which have caused the majority of scholars to conclude, for example, that:

It is not possible to accommodate a truly biblical Exodus in secular Egyptian history anywhere near the traditional biblical date for this event,

No city existed at Jericho at the traditional biblical date for the Conquest, and

No city existed at Ai at the traditional biblical date for the destruction of that city by Joshua, nor had a city existed there for many centuries prior to that date.

The second conservative category takes a low view of biblical chronology, but a high view in the other three categories. Those who hold to the "late date" for the Exodus (i.e., 13th century b.c.) fall into this category. This approach treats the biblical chronological data in a somewhat cavalier, certainly non-literal, manner, and redates the biblical history more or less at will to bring about what are felt to be better correlations with archaeology. This approach was much more popular in the past than it is today. Much archaeological work has been done since the "late date" theory was first proposed a number of decades ago, and many scholars now feel that these more recent data have falsified this theory. In addition, many conservative scholars have rejected this approach because they are uncomfortable with its non-literal treatment of the biblical text.

The third conservative category takes a low view of secular chronologies and a high view in the other areas. It attempts to correlate biblical history with archaeology by radically changing the structure of accepted secular chronologies. The chronology of Egypt is a favorite candidate for revision in most of these schemes. Those advocating such revisions have produced some interesting historical correlations. However, this approach has been rejected by nearly all scholars because they feel that available chronological data, both historical (e.g., king lists) and physical (e.g., radiocarbon), are meaningful and legitimate within the historical period (i.e., last 5,000 years), and they further feel that these data prohibit the revisions of secular chronology proposed by the advocates of this approach.

These last three categories cover the field of conservative thinking to the present time. They have given rise to three schools of thought, each of which contains many devout and dedicated Christian conservatives within its ranks. Nonetheless, the views of Old Testament chronology and, hence, history advanced by these three schools are mutually exclusive, so that the only harmony which has been possible between advocates of differing views to the present time has been of the sort in which people agree to disagree. There presently exists a standoff between these different schools of thought, which is, obviously, a less than satisfactory situation. Perhaps the time is right for something new.

I have been more or less totally preoccupied with the question of the proper relationship between biblical and secular chronologies of earth history for over fifteen years now. This question motivated my choice of Ph.D. program in the early eighties, and the ability to research this question without impediment has motivated all subsequent "career" decisions.

Several years ago I was led, somewhat circuitously, to suspect that the current disharmony between the Old Testament and secular studies prior to about 1000 b.c. might be a symptom of an underlying biblical chronological problem. Much subsequent research has confirmed my suspicion. In this book I present a new approach to Old Testament chronology which restores harmony between the secular data and the sacred history bearing on the patriarchs and the founding of the nation of Israel. This approach is totally unique, and it cannot be fit into any of the four categories above. It initiates a fourth conservative category, which maintains a high view in all four of the above areas.

The derivation and subsequent application of my new chronology necessarily involves a significant excursion into the field of biblical archaeology. The reader needs to be aware that I am not a biblical archaeologist. I am a physicist, and my expertise lies only in the field of chronology, with emphasis particularly on physical methods of dating the past such as radiocarbon. Consequently, I must rely on what others, who are trained in biblical archaeology, have published about their field and its results. I have no first-hand access to the raw archaeological data, and lack the training necessary to draw reliable conclusions from it even if I did.

Fortunately, this is not a problem in the present study. Our excursion into biblical archaeology does not require or utilize detailed technical analyses of pottery fragments, awareness of subtle interpretive nuances, or anything of the sort, as we will see below. We are only interested in general trends and large-scale features.

Fundamentally, however, this is not a book about biblical archaeology; it is a book about biblical and secular chronologies, and this should not be lost sight of by the reader.

I am a Bible-believing conservative Christian, and have written this volume from a conservative evangelical presuppositional basis. I hold to the inerrancy of Scripture in the autographs, and in logical consequence of this belief this work presupposes the historicity of the Old Testament. That is, it is assumed that the Old Testament narratives, from Genesis onward, which purport to be recounting real history, are simply, accurately doing so. The problem to be solved, then, is why this is not immediately apparent when one compares pre-monarchical biblical history and archaeology. The solution to this problem is the subject of this book.

A peculiar phenomenon presents itself when one compares the findings of modern archaeology to the record of the past found in the Old Testament. This phenomenon is best illustrated by the following exercise, which anyone who has access to a good set of Bible encyclopedias can carry out in a single afternoon.

Exercise: Find at least two dozen historical persons who are mentioned both in the Old Testament and in some ancient secular writing uncovered by the archaeologist. (Individuals of international significance, such as kings, are the most obvious candidates.) Do not include any individuals whose secular identification is disputed by conservative scholars. List these by name in order of their historical date.

Here is a typical list, consisting of twenty-five kings of antiquity.

Shishak (Sheshonq I, king of Egypt: ca. 945-924 b.c.); raids Israel and Judah after Solomon's death (1 K 14:25-28)

Omri (king of Israel: ca. 885-874 b.c.); mentioned by Mesha king of Moab in the Moabite Stone which tells of Omri's oppression of Moab

Ahab (king of Israel: ca. 874-853 b.c.); mentioned in the Monolith Inscription of Shalmaneser III as participant in battle at Qarqar (854 b.c.)

Mesha (Mesha, king of Moab: ca. 850 b.c.); pays tribute to Ahab (2 K 3:4)

Ben-hadad (Ben-hadad II, king of Aram: ca. 860-843 b.c.); fights against Ahab (1 K 20:1)

Hazael (Hazael, king of Aram: ca. 843-798 b.c.); takes territory belonging to Israel (2 K 10:32)

Jehu (king of Israel: ca. 841-814 b.c.); pictured and named on Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III as paying tribute

Ben-hadad (Ben-hadad III, king of Aram: ca. 796-770 b.c.); loses to Jehoash king of Israel three times in fulfillment of Elisha's prophecy (2 K 13:25)

Menahem (king of Israel: ca. 752-742 b.c.); mentioned in Tiglath-pileser III's annals as paying tribute

Pekah (king of Israel: ca. 752-732 b.c.); mentioned in Tiglath-pileser III's annals as being deposed

Pul (Tiglath-Pileser III, king of Assyria: ca. 745-727 b.c.); collects tribute from Menahem, king of Israel (2 K 15:19)

Rezin (Rezin, king of Aram: ca. 740-732 b.c.); wages war with Pekah king of Israel against Jerusalem (2 K 16:5)

Hoshea (king of Israel: ca. 732-723 b.c.); mentioned in Tiglath-pileser III's annals as replacing Pekah

Shalmaneser (Shalmaneser V, king of Assyria: ca. 727-722 b.c.); besieges Samaria (2 K 18:9)

Merodach-Baladin (Marduk-apla-iddina, king of Babylon: ca. 722-710 b.c.); sends envoys to congratulate Hezekiah on recovery from illness (2 K 20:12)

Hezekiah (king of Judah: ca. 715-686 b.c.); mentioned in Sennacherib's annals as besieged in Jerusalem

Sennacherib (Sennacherib, king of Assyria and Babylonia: ca. 705-681 b.c.); captures cities of Judah during reign of Hezekiah (2 K 18:13)

Mannasseh (king of Judah: ca. 696-642 b.c.); mentioned in Ashurbanipal's annals as paying tribute

Pharaoh Neco (Neco II, king of Egypt: ca. 610-595 b.c.); kills king Josiah 609 b.c. (2 K 23:29)

Nebuchadnezzar (Nebuchadrezzar, king of Babylon: ca. 605-562 b.c.); took Jerusalem and captured king Jehoiachin March 16, 597 b.c. (2 K 24:10-16)

Evil-marodach (Awil-Marduk, king of Babylon: ca. 561-560 b.c.); treats king Jehoiachin kindly (2 K 25:27-30)

Cyrus (Cyrus the Great, king of Persia: ca. 559-530 b.c.); orders rebuilding of temple (Ezra 1:1-4)

Darius (Darius the Great, king of Persia: ca. 521-486 b.c.); authorizes resumption of work on temple (Ezra 6:1-12)

Ahasuerus (Xerxes I, king of Persia: ca. 486-465 b.c.); husband of queen Esther (Esther 1:1)

Artaxerxes (Artaxerxes I Longimanus, king of Persia: ca. 464-424 b.c.); authorizes Ezra to visit Jerusalem (Ezra 7)

This list does not exhaust every possibility, but it is sufficiently large for the present purpose. It illustrates two important things. First, archaeology apparently is completely capable of corroborating the existence of biblical historical persons. Each entry in this list provides one instance in which the results of archaeology (in this case, the unearthing of ancient stone monuments and wall coverings containing writing) have unambiguously confirmed biblical historicity.

Second, note that the dates of the historical individuals in this list span only a single period of time, roughly 500 years long, near the beginning of the first millennium b.c. This property will be observed in any such list. The reason for the absence of dates in most of the second half of the first millennium b.c. is no mystery, of course. This is due to the centuries-long biblical historical gap between the Old Testament and the New Testament. But the reason for the complete absence of archaeological confirmation of biblical persons for all times much before the first millennium b.c. is not at all obvious.

This is the peculiar phenomenon which was mentioned above. The fact is that not even one biblical person has ever been unambiguously identified in any secular historical writing much before the origin of the monarchy in Israel (which commences about 1000 b.c.). Why? How does it come about that one can easily find one archaeological confirmation of a biblical individual every twenty years on average in the first half of the first millennium b.c., and yet not be able to find even a single such confirmation in a thousand years much prior to the first millennium? Why should such a contrast exist between the first millennium b.c. and all earlier times?

We would not expect all of the people who are mentioned in the Bible before the first millennium b.c. to be found in secular historical source documents, of course, any more than we would expect every biblical person of the first millennium to be found. Archaeology does have its limitations. But surely at least one individual from these earlier millennia should have been positively and unambiguously identified by now.

It cannot be supposed that this contrast is due to a lack of secular written sources prior to the first millennium b.c. A very large number of ancient documents have been unearthed belonging to earlier millennia. Examples include those from Ugarit which date to the 13th and 14th centuries b.c., the Amarna tablets from the 14th century b.c., and the Ebla tablets from the third millennium b.c.

Nor is it reasonable to suppose that this problem is due to a lack of people of international significance in the Bible before 1000 b.c. Many examples to the contrary can be given. There is Joseph, for example, second only to the pharaoh of Egypt, as well as the pharaoh whom he served. There is the pharaoh who oppressed the Israelites in Egypt and the pharaoh of the Exodus. There is Moses, raised in pharaoh's house, and under whose leadership the mighty Egypt was brought to its knees and the nation of Israel born. There is Joshua, who destroyed seven nations in the land of Canaan. Numerous judges of the nation of Israel, such as Deborah and Samson, could be mentioned, and these had contacts with outside kings, of whom there were plenty at these earlier times in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the other nations surrounding Palestine – biblical individuals such as Eglon king of Moab and Cushan-rishathaim king of Mesopotamia. The list of candidates is not lacking in regard to its number of prospects.

The problem is real, and it is truly peculiar. It is further accentuated by considering other aspects of biblical history. Generally speaking, it is not difficult to find unambiguous extra-biblical support for even minor biblical incidents in the first millennium b.c., while it seems impossible to find such support for even the most major biblical incidents of the preceding millennia.

For example, the story has circulated widely of the ease with which Yigael Yadin discovered Solomon's gateway at Gezer. Yadin noted that 1 Kings 9:15 mentioned three cities together at which Solomon had conducted building projects – Hazor, Megiddo, and Gezer. Yadin had discovered a Solomonic period gateway at Hazor, and noted that its architecture was similar to Solomon's gateway at Megiddo. He reasoned, on the basis of 1 Kings 9:15, that a third similar gateway should be found at Gezer, and subsequent excavation proved him right.

This sort of discovery, not uncommon in the first millennium b.c., is entirely absent from the earlier millennia of biblical history. For example, the walls which fell before Joshua at Jericho have never been unambiguously identified. As mentioned earlier, the plain sense of the archaeological data at Jericho seems to say that no city even existed at Jericho at the dates scholars assign to the Conquest. And a similar problem holds at Ai, the second city of the Conquest. In fact, similar problems exist throughout the pre-monarchical period of biblical history. The contrast between the first millennium b.c. and all earlier times is striking.

Why should such a contrast exist? How is it possible to find the remains of all three, relatively insignificant gateways built by Solomon nearly 3,000 years ago, and not be able to find any remains of entire cities supposed to have existed less than 500 years earlier? Something is clearly wrong at a very fundamental level.

I believe this phenomenon is merely one of the more obvious manifestations of an underlying problem in the area of biblical chronology. Simply stated, it appears to me that a subtle error has consistently been incorporated into the calculations of all Christian scholars through the centuries who have used biblical numerical data to compute the dates of biblical historical events (men like Bishop Ussher, for example). This error occurs at a single point in biblical chronology, early in the first millennium b.c., causing the conventional dates of all biblical historical events and individuals prior to Eli and Samuel (i.e., prior to about 1100 b.c.) to be seriously incorrect. The natural result of this error is that biblical and secular history are not properly synchronized in the second millennium as well as at all earlier times, prohibiting the discovery of any real synchronisms between them – including archaeological confirmation of any biblical individuals. This is why the Exodus has never been located in secular Egyptian history, and why the Conquest has not been found at Jericho and Ai and a host of other sites in Palestine where it should be evident. Everybody has been looking at the wrong time.

I believe the potential presence of such a problem is discernible from evidence internal to the Bible alone, as will be shown in the next chapter. However, it is the amassed results of recent decades of archaeological research which make the problem and its solution most obvious (through comparisons of the sort we have carried out above), and the discussion will necessarily turn in the direction of biblical archaeology in subsequent chapters. The fact that much of the extra-biblical information which we will be considering was unavailable until recent decades is why this chronological problem has gone unnoticed and uncorrected for such a long time.

The biblical chronologist has always been confronted with conflicting biblical chronological data in the pre-monarchical time period (i.e., before the period of the Israelite kings, which commences with Saul ca. 1050 b.c.). The conflict is between 1 Kings 6:1, which states:

Now it came about in the four hundred and eightieth year after the sons of Israel came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon's reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv which is the second month, that he began to build the house of the Lord. (NASB)and several other passages in Judges and 1 Samuel which seem to imply a longer time than 480 years between the Exodus and Solomon.

This conflict is easily seen by adding up the well-known 40 years of wilderness wandering, 410 years of alternating periods of oppression and deliverance recorded in the book of Judges, 40 years for the career of Eli, 40 years for the reign of Saul, and 40 years for the reign of David. This already totals 570 years, though it does not include the time during which Joshua led Israel, nor the career of Samuel, and these two, while not specified biblically, must certainly total to something greater than 30 years (they probably total close to 80 years, in fact). Thus, the biblical stipulation of 480 years from the Exodus to Solomon given in 1 Kings 6:1 conflicts with the greater than 600 year total for this same time period which one can calculate from chronological data given elsewhere in the Bible.

It is possible, of course, to get around this difficulty by assuming the chronological data given in Judges must refer to overlapping rather than consecutive time periods. This, in fact, has been the routine traditional approach since well before Ussher, and our familiarity with such an approach may cause us to overlook the fact that these two independent biblical chronological calculations do not give the same answer when both are simply taken at face value.

The assumption of overlapping judgeships is both extra-biblical and ad hoc. While it does the job of bringing about apparent harmony within the pages of Scripture, what assurance have we that it is the right way of doing so?

There are two other exclusively biblical considerations which seem to hint at a quite different solution.

The fact that both Samson and Samuel are seen to be contending with Philistines is often presented as evidence in support of the continuity or contemporaneity of the careers of these two judges. But the Philistines are an enduring fixture in the biblical history of Palestine (they are present there from the time of Abraham through the time of Jeremiah), and armed conflict between the Philistines and the Israelites is hardly a unique phenomenon in the pages of Scripture.

Conflict with the Philistines is evident early in the book of Judges under the leadership of Shamgar (Judges 3:31). It appears again, over 100 years later, after the tenure of the judge Jair (Judges 10:7,8). And it is seen again, several generations later, in the time of Samson (Judges 13:1-16:31). The Philistine conflicts with Saul and David are generally familiar; much more so than the Philistine invasion of Judah over 100 years later in the time of Jehoram (2 Chronicles 21:16) or the Philistine wars conducted by Uzziah yet another 100 years later (2 Chronicles 26:6).

Conflict between the Israelites and Philistines is a recurring phenomenon in biblical history, with numerous incidents spanning many centuries by any reasonable chronology. Thus, the fact that both Samson and Samuel struggled with Philistines seems less than adequate grounds to judge them contemporaries.

Other internal biblical evidence argues for a clean break, historically speaking, between the end of Judges and the beginning of 1 Samuel. Notice that the judge, Eli, who appears in 1 Samuel, is not mentioned in Judges – though he judged Israel 40 years (4:18) and lived to be ninety-eight years of age (4:15) – and neither is Samuel. Furthermore, Samson, the final judge found in the book of Judges, is not mentioned in 1 Samuel.

Indeed, there seems some indication that a fairly lengthy gap may separate these two books. In 1 Samuel we are immediately confronted with the fact that the tabernacle has evidently been built into a more permanent structure at Shiloh, with doorposts (1:9), doors (3:15), and sleeping quarters (3:3). It is no longer referred to as "tent" or "tabernacle" but is consistently called "the temple". Though this seems the status quo in 1 Samuel, it is without introduction or precedent in Judges.

These facts do not favor a compression of the chronology of the period of the judges. Rather, they go in the opposite direction, suggesting the need for more time.

Another hint that a solution for this section of Old Testament chronology different from the traditional one mentioned above may be in order can be found in Acts 13, the only New Testament passage pertinent to this issue. In this passage Paul gives a recitation of Israel's history (Acts 13:16-22) in which he includes a chronological outline. Here, if anywhere, one might hope to find unambiguous endorsement of the 480 years of 1 Kings 6:1. However, exactly the opposite appears. In the King James Version we find the following translation of a portion of this Acts passage:

And about the time of forty years suffered he their manners in the wilderness. And when he had destroyed seven nations in the land of Chanaan, he divided their land to them by lot. And after that he gave unto them judges about the space of four hundred and fifty years, until Samuel the prophet.If this is taken literally it specifies 450 years as the span of time from Othniel, the first Judge, to Samuel, the final Judge. This works out very well in terms of the chronology of all of the known judges (including the tenure of Eli which is recorded in 1 Samuel) which totals to exactly 450 years. However, it clearly contradicts the 480 years from the Exodus to Solomon given in 1 Kings 6:1.

More ancient Greek manuscripts than those which the King James translation was based upon order the phrases differently in this passage, and this alters the chronology relative to that which the King James presents. (These more ancient manuscripts were unknown to the translators of the King James Version.) Most modern translations follow the reading of the earlier manuscripts in this verse. For example, the American Standard Version of 1901 reads:

And for about the time of forty years as a nursing-father bare he them in the wilderness. And when he had destroyed seven nations in the land of Canaan, he gave them their land for an inheritance, for about four hundred and fifty years: and after these things he gave them judges until Samuel the prophet.and the New English Bible reads:

For some forty years he bore with their conduct in the desert. Then in the Canaanite country he overthrew seven nations, whose lands he gave them to be their heritage for some four hundred and fifty years, and afterwards appointed judges for them until the time of the prophet Samuel.

These earlier manuscripts seem plainly to say that the Conquest initiated a 450 year period in which the Israelites possessed the promised land, and that this 450 year period was followed by a further period of time of unspecified duration in which judges ruled Israel until the time of Samuel. Thus, the witness of these earlier manuscripts also contradicts the 480 years of 1 Kings 6:1.

This lack of endorsement (or even blatant contradiction) of the 480 years of 1 Kings 6:1, regardless of choice of original Greek manuscript, is, at the very least, curious. It should caution us against an uncritical acceptance of the 480 years of 1 Kings 6:1.

There is yet another hint in this passage. It surfaces when we take the reading of the more ancient manuscripts literally.

The great weight of modern scholarship seems to side with the more ancient manuscripts in this instance (as is reflected in more modern translations and commentaries), so this earlier reading needs to be taken seriously. The reason why modern scholars side with the earlier reading is not only that the more ancient texts are earlier (though this is an important consideration), but also because the reading of these more ancient manuscripts is the more difficult of the two to understand. An important rule in textual criticism is that the more difficult of two readings is to be preferred. The rationale for this is that a scribe would be more likely to alter the text to smooth an apparent difficulty for his audience than he would be to alter it to make an already smooth reading more difficult.

In the case of Acts 13:19&20 the earlier texts present the more difficult reading because they seem, to the mind conditioned by the traditional chronology, to be stating a chronological/historical absurdity. That is, they seem to be injecting 450 years between the Conquest and the beginning of the period of the Judges. That this is completely impossible is obvious in a number of ways, including, for example, the fact that Othniel, the first judge, was married to the daughter of Caleb (see Judges 1:11-15), who was, you will no doubt recall, one of the ten spies sent out by Moses to spy out the land of Canaan soon after the Exodus. It is reasonable to suppose that the 450 years may have been moved to the position in which it is found in the later manuscripts to avoid this apparent chronological absurdity.

However, when the reading of the earlier manuscripts is unconstrained by traditional assumptions, it is found that there is another, completely valid way of understanding this reading which does not encounter this absurdity. Notice that the earlier reading does not exclude the possibility that judges were also appointed over Israel during the 450 years which followed the Conquest. To illustrate this, suppose I say, "I went to the store and bought a loaf of bread, and afterwards I drove home." From this statement alone you cannot determine whether I drove to the store or walked to the store (where my car was already parked); both possibilities are left open. Similarly, when these earlier readings say "and afterwards appointed judges for them until the time of the prophet Samuel", we cannot say whether judges had also been appointed in the earlier 450 years or not; both possibilities are left open.

From other biblical information, discussed above, we find that it is impossible for this phrase to mean that judges only began to be appointed 450 years after the Conquest, so this possibility can be ruled out. The other possibility is that judges ruled throughout this 450 years as well as afterwards until the time of Samuel. In this possibility the 450 year figure is comprised of an estimated 40 years of leadership in Canaan under Joshua and "the elders that outlived Joshua" (see Judges 2:7) and the 410 years of oppressions and deliverances detailed in Judges. Thus, this possibility implies the existence of a biblical/historical gap between the end of the book of Judges and the beginning of 1 Samuel during which the period of the judges carried on.

This possibility, while certainly non-traditional, does not encounter any biblical historical/chronological absurdities, and it makes Paul's train of thought quite easy to follow. It can now be outlined as shown below and in Figure 3.1.

There was a 40 year period of wandering in the desert, which we are told about in the closing books of the Pentateuch.

This was followed by the initial Conquest of the land under Joshua, which we are told about in the book of Joshua.

This was followed by the approximately 450 year period which we are told about in the book of Judges.

This was followed by a further period of time during which judges continued to rule the nation, the duration of which cannot be specified because the Old Testament doesn't record a history of this period in any book.

This interval of silence terminates with the beginning of 1 Samuel in which book we learn about the final judges, Eli and Samuel.

|

The fact that the chronology of Judges, the apparent gap between Judges and 1 Samuel evident in their respective historical narratives, and Paul's statements in Acts, can be regarded as presenting an internally cohesive view of this section of biblical history, different from the traditional view, seems adequate grounds to call into question the veracity of the traditional view. Each of these biblical considerations is consistent with a new chronology for this section in which the approximate 450 years of Joshua/Judges is followed by an unspecified number of years between Judges and 1 Samuel during which time judges whose careers are not recorded in the Old Testament continued to lead the nation of Israel. All that stands against this view biblically is a single number, the "480" of 1 Kings 6:1. Is it possible that this number may not be correct – that the text of 1 Kings 6:1 as it presently reads may not be a faithful copy of the original – and that this alternative view might, in fact, be the truth?

These biblical considerations certainly do not, by themselves, demand a new approach to this portion of biblical chronology. It is the results of biblical archaeology – such as the problem of the missing biblical persons of the last chapter, and many additional problems which we will see in subsequent chapters – which demand a new approach. But they do hint, however gently, that a previously overlooked, non-traditional yet Bible-honoring alternative chronology may exist. Those who love the Word of God, find the fact of its historicity worth being a bit challenged over, and value the truth more than human tradition, will certainly wish to explore this possibility further.

In the previous chapter we saw that certain biblical considerations suggest the possibility that there may be some problem with the 480 years of 1 Kings 6:1. Since God is the ultimate author of Scripture, and since God does not make mistakes, it follows that there was no problem with 1 Kings 6:1 as it was given originally. But is the number which presently appears in our modern Bibles in 1 Kings 6:1 a faithful copy of the original? Could a copy error have been made at some point in the past which changed the number in 1 Kings 6:1 so that the present "480 years" is not what was originally there? Since this work is likely to be read by a number of Christian laypersons who have not had opportunity to study about the process by which the Old Testament was transmitted to the present, I feel it is necessary to make a few comments about copy errors in general before proceeding. First, please note that copy errors are a matter of textual preservation only; they have nothing to do with biblical inerrancy. Biblical inerrancy teaches that God supernaturally caused the autographs of Scripture to be composed without any error of fact or content in any area. Textual preservation is a different matter; its concern is with the process by which the Bible was hand copied by scribes from scroll to scroll down through the centuries and millennia following the giving of the original text. This copying process appears generally to have been carried out by meticulous and devout individuals, but it was not supernaturally kept free of the sorts of inadvertent mistakes one would expect to find when documents are hand copied.

When first introduced to the possibility of copy errors in the present text of Scripture many people naturally wonder how we can be confident we have the original reading anywhere in the Bible. The most objective answer to this question comes from a study of the ancient copies of the Bible which we presently possess, such as the famous Dead Sea Scrolls. These reveal that, whereas differences do exist between these various ancient copies (that is, they show that copy errors were made by the scribes of the past), these differences are relatively few and generally very minor. There is no possibility of wholesale corruption of the original text; all of the available evidence testifies to the fact that the text as we have received it is remarkably faithful to the original.

Because this is the case it is a very good approximation to the truth to treat the modern text as if it were equivalent to the original, and it is not uncommon for Christians to do so. Only in rare instances, such as the present case, is it necessary to remind ourselves that this is an approximation only, and to set this assumed equivalence aside for the sake of a more complete understanding of a particular passage.

It is essential that we be willing to set this assumption aside in the present case, because it is nothing less than the historicity of the Bible which is at stake. If, for example, Ai was not, in fact, defeated by Joshua, as is now openly, unabashedly claimed on the basis of archaeological excavations at Ai (see, for example, [47]), then the Bible is not correct when it tells us about history. And if the Bible is not correct about history, then the doctrine of inerrancy falls to the ground. And with the loss of inerrancy true Christianity must also collapse. If we are to be able to offer an effective apologetic for the true gospel before knowledgeable twentieth century men and women we must be able to defend the historicity of the Bible, and to do this we must first get our chronology of the Bible right.

But not every claim that a copy error exists in the present text should be taken seriously, by any means. The question of when such a claim is justified has received careful consideration by conservative Bible scholars, partly in response to a cavalier attitude toward textual emendation apparent in some circles, especially during the previous generation. Archer [37, 382, pages 60 and 61] lists five rules, credited to Ernst Würthwein, dealing with this matter and comments:

By means of this careful formula, Würthwein attempts to set up a method of objectivity and scientific procedure that will eliminate much of the reckless and ill-considered emendation which has too often passed for bona fide textual criticism.

I now want to apply these rules to the case of this single number in 1 Kings 6:1 to show that, according to the usual rules, my suggestion that there may be a copy error in 1 Kings 6:1 should be regarded as a legitimate one and given serious consideration. Of these five rules, only the first and fourth are applicable in the current context. These two rules are:

1. Where the MT [Masoretic Text] and the other witnesses offer the same text and it is an intelligible and sensible reading, it is inadmissable to reject this reading and resort to conjecture (as too many critics have done).

4. Where neither the MT nor the other witnesses offer a possible or probable text, conjecture may legitimately be resorted to. But such a conjecture should try to restore a reading as close as possible to the corrupted one itself, with due consideration for the well-known causes of textual corruption.

In the case of 1 Kings 6:1 there is a Septuagint variant which reads "440" rather than "480". Beyond this the "480" of 1 Kings 6:1 is well attested. No variant specifying any number greater than 480 (which is what this new approach requires) has so far come to light. The strong textual attestation of 480 years is, no doubt, the principal reason why the possibility of textual corruption at this point has never previously been seriously pursued. However, according to the rules given above, conjecture (with respect to the text) is permissible if the present text does not provide "an intelligible and sensible reading". I suggest that the present reading of 1 Kings 6:1, while intelligible, is not sensible.

This is best illustrated by considering 1 Samuel 13:1, another problem passage having to do with chronology in the Old Testament. In the King James Version 1 Samuel 13:1 reads:

Saul reigned one year; and when he had reigned two years over Israel, …This seems smooth enough; one would hardly guess that the Hebrew text underlying this translation exhibits some serious difficulties. According to Green's interlinear Hebrew and English Bible [21, page 740] the Hebrew text literally reads:

A son of a year (was) Saul when he became king and two years he reigned over Israel.That is, the text literally says that Saul was a one year old baby when he became king, and that his reign lasted only two years.

Now we know this is not correct from the history afforded us in the Old Testament regarding the reign of Saul; he was at least a young man when he was made king, and his reign had to last much longer than just two years. However, there appears to be no doubt that this verse was intended to convey two important quantitative pieces of information to the reader: Saul's age when he became king, and the length of his reign. Taking all things into consideration modern scholarship is led to the conclusion that some numbers must have been accidently dropped out of the text at some remote time in the past, shortening both Saul's age when he became king and the length of his reign. Gleason Archer [37, 382, page 57] says regarding the first missing number in this verse, for example:

Unfortunately textual criticism does not help us, for both the LXX and the other versions have no numeral here. Apparently the correct number fell out so early in the history of the transmission of this particular text that it was already lost before the third century b.c.

Evidently, the correct translation of the Hebrew as it presently stands should be

Saul was years old when he began to reign, and he reigned over Israel two years.The blanks are both inferred from the fact that the current reading is not sensible as it stands. In modern translations the "sensible reading" clause of rule 1 is, in fact, invoked, and conservative and nonconservative scholars alike do not hesitate to suggest that the text should be emended by the restoration of some appropriate numbers to the text even though there is, in fact, no textual variant supporting the proposed emendations in this case. Thus, the NASB translates this verse as

Saul was forty years old when he began to reign, and he reigned thirty-two years over Israel.And the NEB renders it

Saul was fifty years old when he became king, and he reigned over Israel for twenty-two years.(Both of these translations warn the reader of the underlying textual problems: through the use of italics in the case of the NASB, and through marginal notes in the case of the NEB.)

(Note that the second number in this verse is constrained by the surviving "two" in the present text to read "twenty-two" or "thirty-two". Other historically feasible possibilities such as "twenty-nine" or "thirty-three" are prohibited by rule 4 above.)

I suggest that identical reasoning applies to 1 Kings 6:1. If we take the history which we are given in Scripture between the Exodus and Solomon at face value, it is far too long to fit in a mere 480 years, as was shown in the previous chapter. Thus, it is appropriate to suggest that 1 Kings 6:1 fails to provide a sensible reading, and, on this basis, to conjecture that the text may be corrupt at this point.

Some may be tempted at this point to object that the "480 years" of 1 Kings 6:1 is perfectly sensible as it stands; all that is required is that the chronology of the book of Judges be compressed. But this would obviously be to beg the question. It is the assumption that the "480 years" of 1 Kings 6:1 is correct which is the whole motivation for the compression of Judges, and this assumption cannot be granted since it is, in fact, the question under consideration.

Of course, the lack of textual attestation for a suitable 1 Kings 6:1 variant puts a much larger burden of proof upon other evidence for this postulated textual problem than would normally be the case. Furthermore, it demands that a plausible explanation of how the text came to its present form be supplied, and any suggested restoration of the text must conform to rule 4 above. We hope to meet these requirements adequately below.

However, the important point to grasp at this stage is simply that the suggestion that 1 Kings 6:1 may be corrupt is a legitimate one according to the usual rules of deciding such matters. The text as it currently reads is at odds with other Old Testament chronological information, and just as this opens the door to the possibility of textual corruption in 1 Samuel 13:1, so it does in 1 Kings 6:1. The fact that this other Old Testament chronological information can be arbitrarily rearranged in such a way as to bring about an apparent (though, I would argue, contrived and unnatural) solution to the problem with 1 Kings 6:1 does not mean that this is what should be done, and does not guarantee the validity of the present reading of 1 Kings 6:1 by any means. Responsible scholarship demands that the possibility of textual corruption in 1 Kings 6:1 be taken seriously and explored objectively – to which task we now turn.

The biblical considerations of the previous chapter hinted that the elapsed time between the Exodus and Solomon may be significantly longer than the 480 years presently found in 1 Kings 6:1, and that there may be a portion of Israel's history during the period of the judges between Judges and 1 Samuel for which the Old Testament does not supply any historical record (see Figure 3.1, page 33). The net effect of these two ideas is to loose biblical chronology prior to 1 Samuel from its traditional mooring on the absolute (i.e., b.c./a.d.) time scale and set it adrift. In chronological jargon we say that this section of biblical chronology is "floating". The fundamental problem which needs to be solved in the present chapter is how to re-anchor this floating chronology.

This problem cannot be solved using biblical chronological data alone, as the traditional approach allowed. The anchor for the traditional chronology was the 480 years of 1 Kings 6:1, but this number is specifically suspect in this new approach and must be set aside pending further independent investigation; it cannot be used as an anchor in the present case. The only other possible biblical approach would be to work back through biblical history from Solomon to the Exodus piece by piece, but this route is also blocked in this new approach since we anticipate a gap of unknown length between Judges and 1 Samuel. We can specify a minimum figure of 600 years between the Exodus and Solomon this way, if we assume the numerical data of Judges was meant to provide a straightforward chronology for that book, but this is as far as we can go on biblical data alone. We must turn to some extra-biblical aid to make further quantitative progress.

In principle, any one of several methods might have been employed to provide the anchor point which we are seeking; in practice, only one method can be used in this case. For example, if the Old Testament had recorded certain astronomical observations in this floating, early portion of biblical history we might have been able to use these to compute an absolute date. This method has been used successfully to anchor floating chronologies from some near-eastern countries, but the God-fearing Hebrews did not share the astrological propensities of their neighbors, and the Old Testament is devoid of any such observations.

If we had a piece of a wheel from one of the chariots which was lost in the Red Sea at the time of the Exodus, or Aaron's rod which budded, or any other clearly identified biblical artifact from this early period, the anchor point might be provided by applying radiocarbon dating to this artifact. Though it is not at all impossible that such objects will some day be discovered, we have none at the present time, so this door is also closed to us.

The only method which presently seems possible consists of matching a biblical historical event or sequence of events with its counterpart from biblical archaeology. This is the route which we will follow below.

Biblical archaeology is a vast field today. Some attention must be given to how we can best achieve our goal by an excursion into this field before we launch into it.

Our purpose in turning to biblical archaeology is clear; we wish to correlate some finding from biblical archaeology with its historical counterpart from the book of Judges or some earlier biblical book. This archaeological finding must have a secure absolute date so it can be used as an anchor-point for the early section of biblical chronology we are studying.

It is obvious that some biblical historical events will be more suitable for this purpose than others. The provision of manna in the wilderness is not a good candidate, for example, chiefly because manna was a perishable food item for which no contemporary remains can be expected. Of highest priority then is the matter of preservation. We are, after all, looking for telltale material remains of events which happened more than three and a half millennia ago. Clearly, items made of stone, for example, will be greatly favored for preservation over items made of organic materials such as wood or leather.

A second matter to be taken into account in deciding which biblical historical event we should attempt to locate archaeologically is that of uniqueness. Consider the pitchers which Gideon and his men smashed as they came against the forces of Midian (Judges 7:16-20), for example. These, no doubt, were pottery vessels. The broken fragments from these vessels would be well preserved. Unfortunately, so would fragments of nearly every other pottery vessel which has ever been broken in Palestine. The remains of Gideon's pitchers would be difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish from all of the other potsherds which one would find in the same geographical location, so would not be suitable for our purpose.

A third concern is archaeological prominence. Ancient cities tend to leave behind conspicuous ruins which can be located with relative ease, while the ancient campsites of an army on the move would be much less pronounced and, hence, more difficult to locate and identify unambiguously, as well as less likely to attract archaeological investigation in the first place.

Another criterion we need to consider is biblical detail. Obviously, the more detail we are given about an event biblically, the better. This is especially important when it comes to correct identification of archaeological remains with their corresponding biblical event. The more detail we are given biblically, the greater will be the uniqueness of our archaeological search, and the less ambiguous its results. Returning to Gideon's pitchers, if the Bible had recorded the size, shape, color, etc. of these pitchers the chance of their accurate, unambiguous archaeological identification would obviously have been greatly enhanced.

Finally, we must choose a biblical event whose relative biblical date – within the floating chronology which we are seeking to anchor – is sufficiently well known. It would not do to choose some event from the end of the book of Judges, for example. The historical accounts in Judges 17-21 are given without any clear chronological framework; all we know about these is that they happened sometime during the period when judges ruled over Israel.

Given the above factors as a guide to selection, the choices of the sort of thing we should look for can be narrowed as follows. One would prefer to look for the remains of an ancient city because of the large archaeological prominence of this category. Secondly, our purpose would be best served if the city had been suddenly overwhelmed and destroyed, with a detailed biblical record of the event. (Destruction of a city tends to leave behind large quantities of debris, contributing to preservation of the event archaeologically.) It would also be helpful if the city had been burned during this destruction since preservation and correct identification of the destruction layer are then further enhanced by the durable and easily identified blanket of ashes and charcoal which is left over the ruins.

A factor which can work against preservation of the ruins of a city, and greatly complicate archaeological interpretation, is any subsequent building on the site. Not only does the digging of foundations into previous layers complicate the stratigraphy, but it also admits the possibility of subsequent destruction, thus complicating the task of finding an unambiguous correlation between archaeological remains and the Bible.

Summing up, if we had our choice, we would want to search for the destruction layer of a city which had been violently destroyed and never rebuilt. We would like a considerable amount of information about the city and its destruction to exist in the Bible, and might hope that this information would yield one or more details which would aid in making a correct and unambiguous identification. The time at which the destruction of the city took place relative to biblical chronology should be perfectly clear. And, of course, we would require all of this to be within the early section of biblical history whose floating chronology we are attempting to anchor.

Normally a researcher is not granted such a wish; this time we are. There is one biblical event which comes very close to fulfilling all of these criteria – it is the destruction of the city of Ai by Joshua and his troops.

Ai was the second city to be conquered by Joshua after the crossing of the Jordan river. Its position within the floating section of biblical chronology which we are seeking to anchor is quite precise – it is very near the beginning of the Conquest, about 40 years following the Exodus. Details regarding the destruction of the city are recorded in the eighth chapter of the book of Joshua.

Almost all scholars identify the modern, conspicuous ruins called et-Tell with the biblical Ai. Dissenters have unquestionably been motivated to look elsewhere for Ai by the fact that the archaeology at et-Tell is completely incompatible with the biblical conquest of Ai at the conventional dates (either "early" or "late" dates). Nonetheless, the geographical situation of et-Tell and its topography match that of the biblical Ai very well.

|

Ai is located, biblically, on a hilltop east of, but not far from, Bethel (Genesis 12:8, Joshua 7:2,3). Again, almost all scholars identify Bethel with the modern Beitin. Beitin and et-Tell sit on neighboring hills about two miles apart with Beitin on the west and et-Tell on the east (see Figure 4.1). Joshua 8:11 states that there was a valley to the north of the city; at et-Tell this is matched by a ravine of a seasonal wadi north of the city. It is clear from Figure 4.1 that et-Tell is correctly placed relative to Jericho, from a strategic perspective, for it to have been the next city to have been attacked by Joshua after Jericho.

That Ai was a significant city in Joshua's time is implicit in the biblical narrative in a number of ways. For example, the city had its own king (Joshua 8:14). After the defeat of Ai and the treaty of the Gibeonites with Joshua, the king of Jerusalem was alarmed "because Gibeon was a great city, like one of the royal cities, and because it was greater than Ai" (Joshua 10:2). That Gibeon was compared to Ai, not Jericho, which had also been defeated, suggests that Ai was a larger city than Jericho. In fact, the remains at et-Tell cover about twenty-five acres; excavation at Jericho has shown that it covered only about seven acres. Thus, et-Tell is over three times the size of Jericho, further corroborating its identification as the biblical Ai.

Some might argue that Ai must not have been such a large city since the spies said "they are few" (Joshua 7:3). But the remainder of the biblical account reveals that the spies were certainly wrong. God commanded that the whole army (of at least 40,000 men) should go up against the city (Joshua 8:1), and, in fact, 12,000 inhabitants of Ai and its environs were slain, indicating that Ai was a major city, not just a small town.

We learn from the Bible that the destruction of Ai was violent, the city was burned, and it was not rebuilt for a very long time afterwards (Joshua 8:24,28). At one point in its history et-Tell was violently destroyed and burned, after which there was no occupation of the site for over 1000 years.

Ai was allied with Bethel in some way (Joshua 8:17), but Ai was clearly the only target of military significance. Taken in context with the rest of the conquests in the book of Joshua, the implication is that Ai was a fortified city at this time while Bethel was not. In fact, archaeological excavation at Bethel (the modern Beitin) has revealed that the first walled city at Bethel did not appear until some time following the violent destruction layer at et-Tell.

The Bible records that in the evening on the day in which Ai was destroyed by Joshua, a somewhat unusual monument was erected in Ai by Joshua's army. The account is given in Joshua 8:29.

And he hanged the king of Ai on a tree until evening; and at sunset Joshua gave command and they took his body down from the tree, and threw it at the entrance of the city gate [the LXX reads "cast it into a pit (or trench)", so there is some textual uncertainty here], and raised over it a great heap of stones that stands to this day. (NASB)This is a very significant detail. The evident difficulty of erecting such a heap of stones (recall that Joshua had available 40,000 soldiers for the task) suggests that such monuments should be rare, archaeologically speaking. Judging from excavation reports from other sites, this apparently is the case; Joshua's heap of stones was a highly unique monument. It also has the property of high preservability, and there is thus good reason to suppose this monument might still have existed in modern times when excavation was begun.

In fact, the excavators of et-Tell did find a great heap of stones covering a portion of the ruins [10, page 41]:

The citadel at Ai … was discovered by Marquet-Krause in 1934. Working with 80 to 100 men for "un long mois," [one long month] a six-meter heap of stones was laboriously removed from what proved to be the ruins of Sanctuary A and the citadel.

A six-meter heap of stones is not a small rock-pile; this definitely fits the biblical description of the "great heap of stones" which Joshua and his troops left at Ai following its destruction. The fact that we find such a monument situated immediately above the ruins of a strongly fortified but violently destroyed city which suits the biblical description of Ai in so many other ways as well seems to me to completely guarantee that we have correctly identified the site and the event.

With so much positive evidence confirming the equivalence of the modern et-Tell and the biblical Ai, there is every reason to expect this site to correctly provide the anchor point we are seeking. Secular dating methods (both pottery dating and radiocarbon) reveal that the date of the final destruction of this ancient city is about 2400 b.c., a full millennium earlier than the traditional Conquest date!

Violent destruction overtook the city about 2400 b.c., … No definite identity of the aggressor is known, … The site of Ai was abandoned and left in ruins after its destruction circa 2400 b.c. … the site of Ai lay in ruins until circa 1220 b.c., … [3, page 49](The history of et-Tell, as reconstructed from archaeological reports, is summarized graphically in Figure 4.2.)

|

The idea that a full millennium might be missing from traditional biblical chronology is somewhat shocking at first sight, but there is no mistake apparent in our logic or assumptions to this point, and, thus, no rational way around this implication. All of the archaeological clarity which we had hoped for is found at this site, so the historical picture seems quite plain. There is only one stratigraphic layer which can possibly correspond to the violent destruction and burning followed by a long period of no rebuilding, and it dates to ca. 2400 b.c. Et-Tell suits the biblical data pertaining to Ai very well, and, despite much effort, no other site has ever been found which suits these data at all. Only the date is "wrong", and this, apparently, is all that has ever been "wrong" with the archaeology at this site.

Perhaps some readers are tempted to dismiss the secular archaeological dates at this stage. In fact, there is no rational, objective grounds for doing so. The destruction of the city was initially dated in excess of 2000 b.c. by Marquet-Krause in the mid 1930s on the basis of pottery shards found there. Refinements in pottery dating techniques allowed the date to be more precisely estimated at around 2400 b.c. by the mid 1960s. Radiocarbon dating was invented only in the late 1940s, and has itself gone through a number of refinements of technique over the past forty-five years. Even so, it has an inherent dating uncertainty of about ±100 years when applied to these ancient times, so it has not been able to provide a more precise date for the destruction of the city. It has, however, provided completely independent corroboration of the conclusion already reached by pottery dating at Ai. The radiocarbon results from Ai [11] simply will not admit anything like a thousand year error in the secular dates at this point. When all of the pertinent chronological data are taken into consideration the only reasonable conclusion is that the true date for the destruction of Ai cannot possibly differ from 2400 b.c. by more than about 100 years.

Ai does an excellent job of furnishing the anchor point we are seeking – even if the result is unanticipated. Strictly speaking, nothing more is required to further develop the biblical chronology which results from this new approach. However, the rough date of the Conquest of Ai – our anchor date – has immediate, if somewhat unexpected, implications of its own. Most importantly, it provides an obvious explanation of how the text of 1 Kings 6:1 came to its present form (i.e., "480 years") and immediately suggests how the text should be restored.

The secular date for the destruction of Ai ( ca. 2400 b.c.) is essentially 1,000 years before the traditional biblical date for the Conquest ( ca. 1407 b.c.) which is computed using the "480 years" of 1 Kings 6:1. This suggests the possibility that the original number in 1 Kings 6:1 was "1,480", and that the text of 1 Kings 6:1 has come to its present form through the loss of the leading digit "1". Thus, the problem with 1 Kings 6:1 seems even more similar to that which we saw with 1 Samuel 13:1 previously.

This possibility seems, in fact, quite plausible when examined more closely. In the original Hebrew, "1,480 years" would have been written out in words, probably as it appears in the top row of Figure 4.3.[3] (I have purposely not included any space between words, nor any vowel points in this figure to more closely imitate the text as it probably originally appeared to the ancient copyist.) The similar beginnings of the words "and thousand" and "and four" in Hebrew, would make it easy for the eye of the scribe who was copying the text to skip from the beginning of "and thousand" to the beginning of "and four" as shown by the arrow. This would result in the accidental loss of the "and thousand", giving the present reading, as shown in the bottom row of the figure. This is a minor example of the well-known type of manuscript error called homeoarkton. (See Archer [37, 382, pages 54-57], for example, for a discussion of various types of manuscript errors.)

|

Notice that this suggested restoration of the text of 1 Kings 6:1 satisfies the requirements of rule 4 discussed earlier in this chapter. Specifically, it "restores a reading as close as possible to the corrupted one", and it takes "due consideration for the well-known causes of textual corruption." Thus, though the lack of textual evidence has forced us to conjecture about the nature of the original text, we have satisfied the normal rules governing textual emendation completely in doing so.

Notice also that there is nothing arbitrary at all about the final result. We are completely constrained to the choice of 1,000 as the only possible missing quantity in 1 Kings 6:1 through two considerations. First, the archaeology at Ai demands that this quantity be roughly between 900 and 1,100. Choices outside this range – say 500 or 5,000 – simply won't work because there is no destruction at Ai corresponding to the dates which such choices would predict. Second, once this range of roughly 900 to 1,100 has been established, textual considerations mandate the choice of 1,000. Other choices – such as 999 or 1053 – are disallowed by rule 4 above. (The situation here is once again completely parallel to the emendation of the text in 1 Samuel 13:1 which we saw earlier.) "One thousand" is the only permissible possibility.

Here, then, is a simple explanation of the whole problem of the disharmony between biblical history and archaeology in the pre-monarchical period. "One thousand" was accidently lost from the text of 1 Kings 6:1 hundreds of years b.c. The loss of this millennium seriously desynchronized biblical history and archaeology in the pre-monarchical period, a problem which was only made sufficiently obvious to warrant serious attention by the rise of biblical archaeology in the present century.

If this explanation is correct, then we predict the restoration of harmony between biblical archaeology and biblical history in the pre-monarchical period by the simple inclusion of this "one thousand" in the future computation of pertinent biblical dates. If it is wrong, serious disharmony should result, for it is not possible to insert a full millennium into any chronology where it does not belong and find resulting harmony between it and actual field data. In subsequent chapters we will see that this simple explanation does, in fact, work out very well.