| |

| Volume 13, Number 1 | February 7, 2023 |

I have labored over the route of the Exodus on and off for years. The ultimate goal is to be able to draw on a map the true path taken by the Israelites from Egypt to Canaan following the Exodus. My initial work on this was published in the January/February 1996 issue of this research newsletter.[1] Now here we are in 2023, twenty-seven years later.

My primary goal back in 1996 was to harmonize biblical and secular chronologies of earth history. Achieving that goal would absorb most of my available time for the next four years. Reconstruction of the route of the Exodus was a fascinating related problem I could only toy with along the way.

By 2000, the goal of harmonizing biblical and secular chronologies of earth history having been achieved, I was free to launch in a new direction. I chose to focus on solving the mystery of aging. A solution to this mystery was by far the greatest humanitarian need of the modern world.

My previous research, set in the Bible's remotest ages, had positioned me uniquely with respect to this problem. I knew from this research, more cogently than any person alive, that prior to about 3500 B.C. humans had, in fact, lived over ten times longer than we do today. I also knew, more forcefully and accurately than any person alive, that the Flood was a real historical event of global proportions, and that human longevity had plummeted following that event. It appeared obvious that the Flood had done something to shorten human longevity dramatically. I felt morally constrained by the magnitude of the humanitarian need to put all else aside to determine, if possible, what exactly the Flood had done to bring about this result. Research regarding the route of the Exodus was put on hold as I donned armor, sword, and shield to engage the three-headed dragon known as Aging.

The battle lasted seventeen years.

I had always supposed that once the cause of aging had been elucidated and the cure for aging found, people would clamber over one another to avail themselves of the cure. Who wants to suffer the depredations of aging? I certainly don't.

The choice between staying youthful and growing old is, to me, a no-brainer. Who wants cancer? Who wants heart disease? Who is looking forward to having to live in a nursing home? Not I.

If someone has his heart set on dying more than ten times sooner than our ancient ancestors died, there are much less tortuous ways to accomplish this. Aging seems to me to be a dreadfully protracted way to commit suicide.

It became clear, over a year ago, that many people were experiencing a difficult trust issue with my cure for aging. The marketplace is currently flooded with bogus "anti-aging" products. The consumer is being heavily scammed. In addition, the spirit of the age sees science and the Bible as opposites, pitted against each other. How could the Bible possibly have any say in such an obviously scientific matter as the cause of aging? And how could any real scientist possibly take the Bible seriously? Meanwhile, the cure for aging does demand substantial, sustained trust. Aging disease cannot be instantly halted. Aging is a syndrome of three diseases, two of which respond relatively quickly to the cure, but the remaining disease takes decades to slow down and heal.[2]

Since the discovery of the cure for aging, I have felt, once again, morally obligated to do whatever I could to help people understand the syndrome of diseases we call aging so they could intelligently avail themselves of the cure and sustain confidence in their treatment of aging long term. This effort, in an unexpected way, has brought me back to tackling the route of the Exodus problem once again.

It seemed I might be able to help with the trust issue by showing in an obvious way that the Bible/science method I have always used in my research is trustworthy. The manna mystery—i.e., what, exactly, manna was—seemed the right candidate for such a demonstration.

I had toyed with the manna mystery on and off for years. My earliest notes on it, in the margin of my personal study Bible, are dated September 1, 2005. Early last year I determined to make solving this particular mystery my number one priority in hopes that it might ultimately help the doubtful to get on board with the cure for aging.

The manna mystery is now behind me, as my soon-to-be-available book, Bread from Heaven: The Manna Mystery Solved, shows. The solution of this particular mystery, unlike the solution of the aging mystery, has the great advantage of being immediately, self-evidently true, validating my Bible/science research method as intended. I have been able to synthesize manna in the laboratory. Samples of manna will soon be made available so people can taste and see for themselves what millions of Israelites fed on in the desert some four and a half thousand years ago.

The year invested in solving the manna mystery has set me up to tackle the route of the Exodus once again. To solve the manna mystery, I had to delve into the details of the Israelite encampments in the desert, where manna first appeared. As a result, I learned much about the lifestyle of the Israelites the forty years they spent in the desert, clarifying a number of specifics of the route of the Exodus which were previously obscure. This present article is intended as part of a series documenting my ongoing research into the route of the Exodus as it takes place.

The twenty-seven years which have intervened between my initial work on this problem and this new effort have resulted in one significant technical advantage. Google Maps now greatly simplifies and reduces the burden of cartography associated with the reconstruction of the route of the Exodus.

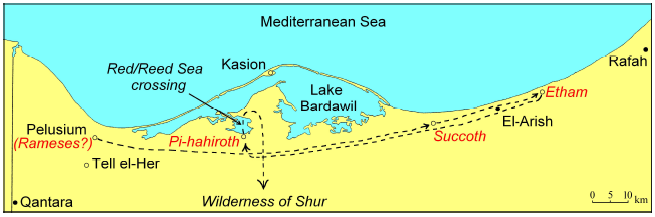

The locations of the first three encampments of the route of the Exodus—Succoth, Etham, and Pi-hahiroth—are revealed by Exodus pottery cataloged during the North Sinai Survey between 1972 and 1982 and reported on by E. D. Oren and Y. Yekutieli in 1990.[3] Figure 1, previously published,[4] shows the locations of these first three encampments and the initial route of the Exodus they imply. Of these three, the Etham encampment is the most archaeologically pronounced. It yielded a remarkable concentration of Exodus pottery shards and other archaeological remains covering a large area.

|

Three items of importance to the reconstruction of Israelite Exodus encampments in general are clarified by the Etham encampment. The first has to do with the physical size of these encampments. The second involves the herds of livestock which accompanied the Israelites. And the third has to do with the climate of the region.

|

This area is defined by the clustering of archaeological sites within it. Oren and Yekutieli describe the numerous archaeological sites they found all along the north Sinai road (modern Route 40) from the Suez to Rafah, including at Etham (which they refer to as the Jiradi region), as follows:

The sites are generally located on the bare surface of clay soil among either active or stable dunes. As a result of intensive eolian deterioration, the sites were found in various degrees of erosion, and the findings were scattered over different levels of the site. … In most of the sites there is no evidence of solid building, and it looks as if the inhabitants lived in booths, tents, or lean-tos. Most sites present some cooking or baking devices; among the findings are remains of 'tabuns' (kilns), bonfires, pockets of ashes as well as stone circles 1–2 meters in diameter, or squares of stones …

Many stone tools were found in the sites which served for pounding and pulverizing, many flint tools and a rich array of ceramics [i.e., pottery]. The sites also yielded bones of various animals, beads, sea shells, and large quantities of broken ostrich eggs.[6]

The size of the Etham encampment is in agreement with the size of the plain which was available for the encampment at the true Mount Sinai—roughly 15 kilometers long by 3 to 4 kilometers wide, as I have previously noted.[7] This computes to between 45 and 60 square kilometers. This agreement suggests that in general the Israelites' desert encampments may be expected to cover 60±10 square kilometers (23±4 square miles).

This size yields a large but reasonable population density for the number of individuals participating in the Exodus.

Now the sons of Israel journeyed from Rameses to Succoth, about six hundred thousand men on foot, aside from children. (Exodus 12:37)The "aside from children" of the above quote intends to communicate that male children (i.e., less than 20 years of age) were not included in this count of men. The count of 600,000 is meant to be of grown men only. It excludes both women and children.

The overwhelming support given to this number elsewhere in the biblical books of Exodus and Numbers has previously been shown.[8] The literalness of this 600,000 number seems beyond reasonable question textually.

If we assume that 50% of the population were female, then the number of grown men and women involved in the Exodus comes to 1.2 million. If we further assume an average of 2.1 children (i.e., sufficient to sustain the population) per each of the potentially reproducing pairs of adults, the result is 1.26 million children. The total population of the Exodus is then 2.46 million, which rounds to two and a half million people. This yields 2.5 million people living on 60 square kilometers of ground, which is 42,000 people per square kilometer. This computes to about 24 square meters (a square roughly 16 feet per side) per person.

Assuming 600,000 households, the result is roughly 100 square meters per household. This is a square roughly 33 feet on a side, large enough to accommodate, in modern terms, a small single wide mobile home, a small yard, a sidewalk and an alleyway.

Apparently, a similar or even larger population density can be found near this same region today.[9]

The Israelites seem neither to have been crammed together nor widely separated in their desert encampments. Thus, one may picture an encampment as a reasonably comfortable tent city.

But one must not imagine a small group of tents. It was a vast tent city. One must imagine 600,000 tents. And a square tent city of 60 square kilometers implies nearly 8 kilometers (nearly 5 miles) per side. To walk from one side of such a tent city to the other side at a brisk pace would take over an hour.

Vast herds of livestock accompanied the Israelites when they left Egypt.

And a mixed multitude also went up with them, along with flocks and herds, a very large number of livestock. (Exodus 12:38)

Where were these herds kept? Were they kept in the encampments? The archaeology at Etham answers these questions.

Another cluster [of archaeological sites], though much sparser, exists about 8 kilometers east of the [Etham] cluster … We surmise that these data indicate that … the group of small sites at the margins of the Jiradi [Etham] cluster mark the remains of herdsmen's encampments …[10]This shows that the herds were not mingled with the people in the encampments. The archaeology at Etham shows that the herds were bedded at night apart from the encampments, on the outskirts of the camp. (They would, of course, have been taken to fresh pasture during the day.) The archaeology at Succoth shows the same pattern.

The climate in the region during the Exodus was less arid than it is today. This is especially important to the question of where in the desert sufficient pasturage to feed the vast herds accompanying the Israelites was to be found.

Today, the deserts of the region are arid and characterized by open soil, being sparsely vegetated everywhere except in wadi beds and oases. At the time of the Exodus, there was clearly more rainfall.

This is evidenced, for example, by data indicating that the Dead Sea surface was approximately 30 feet higher back at that time than it is in modern times.[11] At Etham, it is evidenced by the situation of the encampment.

The main reason for such a large concentration of sites [at Etham] is the fact that this is the ancient location of the estuary of the Nitzana river which was still active [back then].[12]

The estuary at Etham is no longer active today. The estuary of Wadi al-Arish, to the west of Etham, is easily identified on Google Maps[13] and from there the Al-Arish river is traceable for miles in a southeasterly direction into the desert back to its source. In contrast, no estuary of Wadi Nitzana is discernible on Google Maps at Etham today, and the bed of the source of the Nitzana river, visible far to the southeast, disappears into the desert soil only a few miles downstream of Nitzana, many miles from Etham.

It appears that the wilderness in which the Israelites lived for forty years, which presents mainly as bare-ground desert today, may have been more of an open grassland savanna at the time of the Exodus.

Having learned the size of the Israelite encampments, it is possible to outline the probable extent of the encampments at Succoth and Pi-hahiroth working from Oren and Yekutieli's surface survey data. Figure 3 shows the result. The outlines for Pi-hahiroth and Succoth are more approximate than for Etham due to the higher density of archaeological remains at Etham. ◇

|

The Biblical Chronologist is written and edited by Gerald E. Aardsma, a Ph.D. scientist (nuclear physics) with special background in radioisotopic dating methods such as radiocarbon. The Biblical Chronologist has a fourfold purpose: to encourage, enrich, and strengthen the faith of conservative Christians through instruction in biblical chronology and its many implications, to foster informed, up-to-date, scholarly research in this vital field, to communicate current developments and discoveries stemming from biblical chronology in an easily understood manner, and to advance the growth of knowledge via a proper integration of ancient biblical and modern scientific data and ideas. The Biblical Chronologist (ISSN 1081-762X) is published by: Aardsma Research & Publishing Copyright © 2023 by Aardsma Research & Publishing. Scripture quotations taken from the (NASB®) New American Standard Bible®, Copyright© 1960, 1971, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. All rights reserved. www.Lockman.org |

^ Gerald E. Aardsma, "The Route of the Exodus," The Biblical Chronologist 2.1 (January/February 1996): 1–9. www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ Gerald E. Aardsma and Matthew P. Aardsma, Aging: Cause and Cure, 2nd ed. (Loda, IL: Aardsma Research and Publishing, 2021). www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ E. D. Oren and Y. Yekutieli, "North Sinai During the MB I Period—Pastoral Nomadism and Sedentary Settlement," Eretz-Israel 21 (1990): 6–22. (English translation provided by Marganit Weinberger-Rotman.)

^ Gerald E. Aardsma, The Exodus Happened 2450 B.C. (Loda, IL: Aardsma Research and Publishing, 2008). www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ E. D. Oren and Y. Yekutieli, "North Sinai During the MB I Period—Pastoral Nomadism and Sedentary Settlement," Eretz-Israel 21 (1990): 6–7. (English translation provided by Marganit Weinberger-Rotman.)

^ E. D. Oren and Y. Yekutieli, "North Sinai During the MB I Period—Pastoral Nomadism and Sedentary Settlement," Eretz-Israel 21 (1990): 6–22. (English translation provided by Marganit Weinberger-Rotman.)

^ Gerald E. Aardsma, "Yeroham: the True Mount Sinai," The Biblical Chronologist 6.4 (July/August 2000): 4. www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ Gerald E. Aardsma, "Biblical Chronology 101," The Biblical Chronologist 4.5 (September/October 1998): 10–14. www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ www.luminocity3d.org/WorldPopDen//#10/31.1840/ 33.7335 (accessed February 1, 2023).

^ E. D. Oren and Y. Yekutieli, "North Sinai During the MB I Period—Pastoral Nomadism and Sedentary Settlement," Eretz-Israel 21 (1990): 6–22. (English translation provided by Marganit Weinberger-Rotman.)

^ Gerald E. Aardsma, Bread from Heaven: The Manna Mystery Solved (Loda, IL: Aardsma Research and Publishing, 2023), Appendix A. www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ E. D. Oren and Y. Yekutieli, "North Sinai During the MB I Period—Pastoral Nomadism and Sedentary Settlement," Eretz-Israel 21 (1990): 6–22. (English translation provided by Marganit Weinberger-Rotman.)

^ Its (latitude, longitude) coordinates are (31.145794, 33.806735).